Introduction

TL;DR: With a single Ryzen 9 7950X, I pushed ~11.5k valid proofs/sec (~0.68–0.70M in 60s) using ~50% CPU into Anubis at its highest difficulty with Anubis challenge verification choking on mutex-wakeup thrashing-not ideal when Anubis also acts as a reverse-proxy that in real deployments have to forward all traffic on top of that.

Anubis running on the same machine in browser using multiple workers (concurrent is not tunable) produces ~150 kH/s when we achieved ~1.5 GH/s on benchmark.

You can try this out on a public instance running on a $10/month VPS at a solid 80+ MH/s single-threaded.

What is Anubis?

Anubis is a bot-deterrent system that uses PoW (Proof of Work) with the intention of discouraging bots from accessing a website.

Check out the official repo for more details.

The gist was:

- This is branded as a “stop-gap” measure to filter out aggressive or unwanted bot traffic.

- This is a reverse-proxy middleware (i.e. if Anubis dies or gets severely degraded, the service will degrade at least as much if not more).

- While the author admitted bypassing it is usually trivial, they still repeatedly double-down on the narrative of being a “security” measure-refusing to publish open specs, benchmarks, or standalone PoW provers. I also failed to find any attacker modeling and security assumptions document, in my opinion this is not ideal and easily leads to security by obscurity (which is fragile once the popularity of Anubis becomes a monoculture).

What this is / isn’t

- Not a 0‑day, there are prior works that work just as well if not better for mounting a real attack.

- Not by “bypass.” The author already admits you can skip it without any compute anyways. This is just a tool to emit actual proofs as fast as possible and show the official validation backend is under-optimized for that workload.

- No live instances were harmed during the production of this article, nor do I believe the incremental abuse risk from my solution is significant enough to warrant a preachy disclaimer: real attackers use GPUs for SHA-2 and get 100x+ throughput on top of what I get, not try to figure out “one weird tricks” for CPU.

- My “style guide”: Semi‑educational, semi‑roast, no personal insults. I believe most evaluations and opinions to be based on observed code, comparative measurements, corroboration with official documentation/tickets/blogs and algorithm facts.

Motivation

There are 3 main frustrations and concerns I have as a user:

- It is popular and deployed on many high profile websites such as Kernel.org and Arch Linux. However the code has many known bugs, compatibility issues and misconfiguration foot-guns that lock legitimate users out of the service-coupled with the official stance of refusal to publish specs, it is often impossible for an average user to access the service if the in-browser solver fails.

- It requires users to disable their anti fingerprinting protection like JShelter, and doesn’t give users an opportunity to re-enable them before automatically redirecting them to the website they have never been to before, which can very well hide fingerprinting scripts.

- It is not fundamentally different than using visitors’ browsers to mine cryptocurrency (i.e., in‑page cryptocurrency mining) in terms of externalized compute cost and user experience impact:

- It still is in a miner (and a low-efficiency miner at that, tops out at ~100kH/s when we can do multiple magnitudes more).

- There is a scarcity associated with the reward of mining: permission to access a resource. Visitors pay the cost (battery life, power bill, device lagging and thermals) and servers pocket the gain (lower maintenance cost).

- There is externalization of user cost: While it is not cryptocurrency mining that produces a fungible asset, IMO it is not automatically more “ethical” than a cryptocurrency miner. It is like arguing not paying your worker is slavery but asking somebody to dig a hole in the ground for no reason despite having a tractor available is not—because the hole has no monetary value—that’s not how ethical computing works.

In terms of what role Anubis is supposed to serve, I have one core disagreement with the project:

It seems they clearly have a different product goal as I see it: I see it as a QoS tool that I have ethical concerns over and failed a core objective of knowing what kind of loads are possible, benchmarking against that and degrading gracefully; they see it as a security product that need perfect consistency and recall over specificity. For this reason it is very hard to understand some of their decision (including not using lock-free or probabilistic data structures) and I am not going to claim the backend is “bad”-it’s just not fit for the purpose I see it useful for.

Objective: Performance Characteristics

So I wanted a tool that:

- Gives me a valid proof for: sites that (1) ask for it (2) does not work without JShelter disabled so I am not penalized for being “bot like” just for using a privacy-enhancing extension.

- Try to employ as many optimization tricks as possible to get an adversarial performance number. I believe these numbers and methodology are as useful to an attacker as it is to a defender.

So I did, and it worked better than I expected. With SIMD and only a single 7950X hammering valid proofs at a local Anubis server asking for the most extreme PoW difficulty - “extreme suspicion” ($D=4$), we managed to achieve a proof throughput higher than Anubis verification throughput:

Set up a local Anubis server with policy (remove all other policies except “extreme suspicion”, then change expression to weight >= 0):

| |

Fire up our solver against it:

| |

We managed to get almost 700k proofs stuffed into our local test Anubis setup in 60 seconds (when our capacity is about double that due to Anubis not responding fast enough). We believe that is enough to neutralize or even negate any realistic scraping or DoS “protection” Anubis is designed to provide.

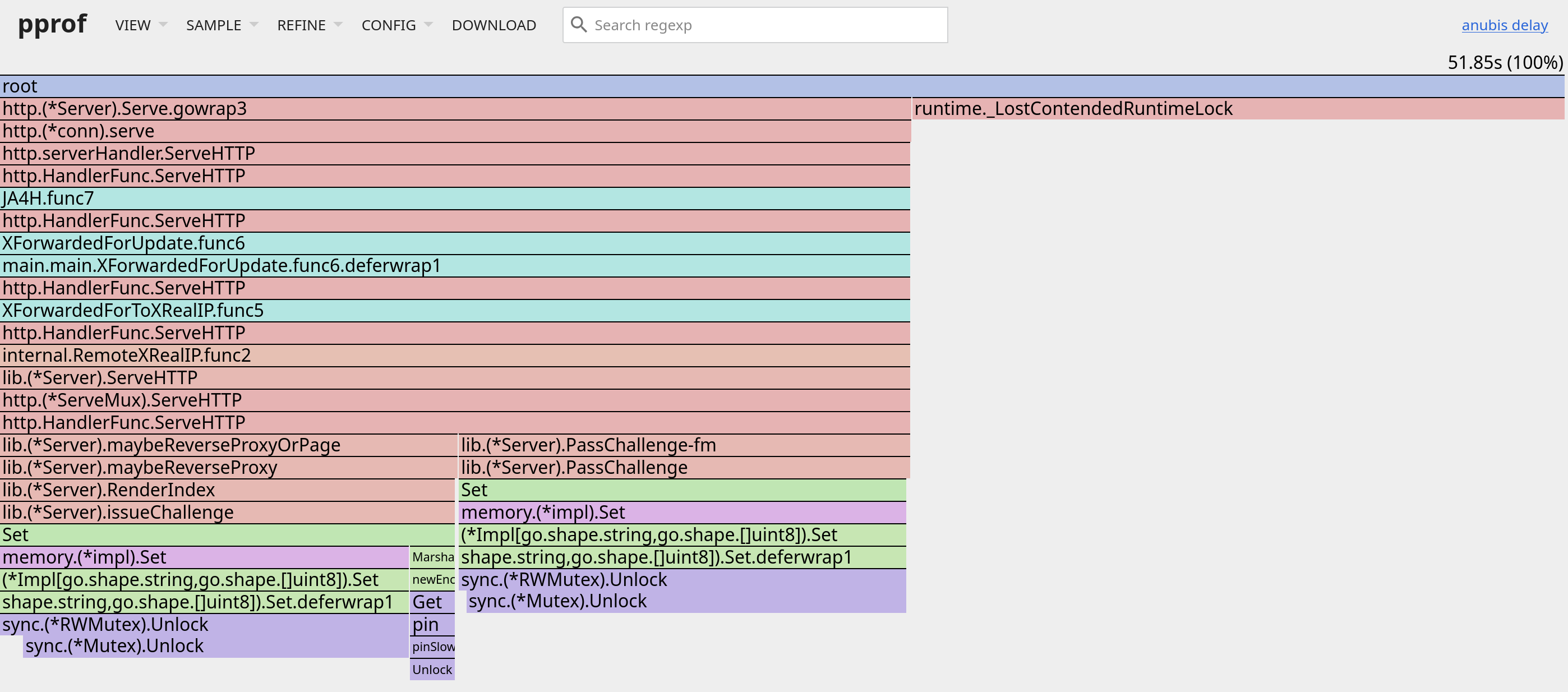

Here’s a Go pprof output showing Anubis struggling 1 with Mutex wakeup thrashing gathered in a dedicated local instrumented build during attack workload (sample rate = 0.001), the above throughput was measured against a non-instrumented build.

Analysis

Anubis’s PoW algorithm

Despite the opaque specification, Anubis follows a relatively standard Hashcash-like construction. It currently has 3 deployed “algorithms” that require computational work:

preact: Use a tiny Preact application to return the SHA-256 of a string: trivial to replicate, not the goal here.fast: Compute $\text{SHA-256}(S | N)$ where $S$ is a server-side salt and $N$ is a nonce encoded as a decimal string in Gointrange (on most machines it is 64-bit) and%dformat. The success criteria is the hash must have at least $D$ leading zero nibbles (i.e. $4D$ leading zero bits). Currently $S$ is always 128 bytes long (although our solver does not depend on that-in fact it can work better for most alternative lengths).slow: Same asfastbut except serve an alternative JS solver to browser-based workers. While they claimed it to be slower thanfast, in my test it varies between different browsers and isn’t always slower. However since the algorithm is the same and this article is mostly about optimizations, we believe focusing on the “fast” version is sufficient.

Establishing a baseline

Before thinking about deploying defense or applying optimization, sanity‑check your box. If these look far off:

- for defenders: this likely isn’t a well tuned defense.

- for attackers: fix thermals/governor/flags first.

| |

Brief Intro to hash-based PoW and SHA-2

SHA-2 is a family of hash functions, here used as a preimage-resistant keyed PRF-you initialize it with a key (salt) and then try to feed it some data, it will return a fixed-length, unpredictable output.

The idea of hash-based PoW was since you cannot predict which input will produce the desired output bit pattern, you will need to brute-force it at a success rate of $1/16^{D}$, which means statistically we have a geometric distribution and characteristic:

- Mean attempts to success: $1 / p = 16^{D}$, 65536 for $D=4$, that’s what a continuous prover will pay overall for a single proof.

- Median attempts to success: $\frac{-1}{\log_2(1-p)}$, about 45425 for $D=4$. That’s the 50% percentile of your site’s visitors’ PoW attempts, with the current JS solver it empirically takes about 1.5s to 10s to complete depending on the browser and CPU, you can grep

kH/sin Anubis codebase or check tickets and blogs to corroborate.

Now let’s delve deeper into the math:

The SHA-2 family is defined in FIPS 180-4 - Secure Hash Standard, which has 3 components from innermost to outermost:

- A Compression Function.

- A Message Schedule.

- A Merkle-Damgård Construction Wrapper.

Merkle-Damgård Construction

The outermost wrapper is the Merkle-Damgård Construction, which prepares the message into fixed-length blocks: for byte-oriented messages, it is defined as: append an 0x80 byte, then pad with null bytes until exactly 8 bytes before the end of a full block, finally write the length of the original message in bits as a 64-bit big-endian integer into the last 8 bytes.

The state variables are initialized with a constant initial hash value. Then, it takes a compression function $f$, the compression function takes input message schedule $M$ (for SHA-2, $M$ has 64 32-bit words) and a set of state variables $H$ (8 32-bit words for SHA-2) and outputs an updated set of state variables $H’$.

Finally, define “update” as: for each block $M_i$, update the state variables using compression function $f$ producing new state variables $\lbrace A, B \cdots H \rbrace$, then perform a “feedforward”: element-wise modular addition $H’_0 = A \boxplus H_0, H’_1 = B \boxplus H_1, \cdots, H’_7 = H \boxplus H_7$.

The output is defined as the concatenation of the state variables $H’_0, H’_1, \cdots, H’_7$ in big-endian order. For example, if $H’_0 = 0x01020304, H’_1 = 0x05060708$ then the hash will start with \x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x07\x08.

Notations are informational and while proofread may contain mistakes and ambiguities, if you want to implement it, I recommend copying directly from the standard.

Message Schedule

Message schedule ingests message blocks and emits a sequence of words. For SHA-2, it ingests 16 32-bit message blocks (big endian order!) and emits 64 32-bit words.

In SHA-256 it is defined as a recursive relation, which is the form we will use in our solver:

$$ W_i = M_i \text{ for } i \in \lbrack 0, 15 \rbrack \\ W_i = \sigma_1(W_{i-2}) + W_{i-7} + \sigma_0(W_{i-15}) + W_{i-16} \text{ for } i \in \lbrack 16, 63 \rbrack $$Compression Function

In SHA-2, the compression function is defined as (page 10 of FIPS 180-4):

$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma_0(x) &= (x \ggg 2) \oplus (x \ggg 13) \oplus (x \ggg 22) \\ \Sigma_1(x) &= (x \ggg 6) \oplus (x \ggg 11) \oplus (x \ggg 25) \\ \text{chi}(x, y, z) &= (x \land y) \oplus (\lnot x \land z) \\ \text{maj}(x, y, z) &= (x \land y) \oplus (x \land z) \oplus (y \land z) \\ \end{aligned} $$Then 64 rounds of computation where $K$ is a 64-element set of 32-bit round constants:

$$ \begin{aligned} T_1 &= H + \Sigma_1(e) + \chi(e, f, g) + K_i + W_i \\ T_2 &= \Sigma_0(a) + \text{maj}(a, b, c) \\ H &= G \\ G &= F \\ F &= E \\ E &= D + T_1 \\ D &= C \\ C &= B \\ B &= A \\ A &= T_1 + T_2 \end{aligned} $$Brief Insights

We can observe these properties which will influence our implementation:

- The algorithm has an ARX-like design with more diversity of operations and an adequate level of inner parallelism.

- $\text{chi}$ and $\text{maj}$ are bitwise ternary logic functions.

- $A$ has the critical path (which gets propagated into $H_0$), then $E$.

- The round constants are directly added to the message schedule and can be hoisted out of the loop.

- All full-block rounds of a message can be precomputed.

- If the message has a constant prefix of length $P$ bytes, then the first $\lfloor \frac{P}{4} \rfloor$ rounds can also be precomputed.

- The first $k$ 32-bit words of the output is only dependent on feedforward terms $H_0, H_1, \cdots, H_{k-1}$, and independent of $H_k$ and beyond.

- Mutating a message intra-block is cheap, mutating a message inter-block is expensive.

- A big-endian/hex-lexicographical order of output hash has the same significance order as comparing hash words $H_0, H_1, \cdots, H_7$ directly (in that order of significance).

Brief Intro to SIMD and AVX-512

SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) is a technique to perform the same operation on multiple data points in parallel. We will use AVX-512 to vectorize the algorithm (which is available on most HEDT and server CPUs after 2019 and many prosumer cloud offerings).

Since the algorithm has a good level of inner parallelism, and we have 32 registers to work with in AVX-512, the most straightforward approach is used: place all 8 states and all 16 message schedule intermediates into 24 registers, then apply vectorized instructions to amortize the cost of computation to 16 independent messages hashed at once.

Additionally, AVX-512 has mask registers: comparisons are directly emitted into mask registers as bitmasks, and kortest instruction allows 1c uop-fused branching on the result.

For this task we can get started with RustCrypto’s sha2 crate, since it is an Apache 2.0 licensed crate we can reuse it under the terms of the license. Simply perform a transpilation of the kernel into AVX-512 intrinsics will get you a pretty competitive baseline:

- Arithmetic is mostly trivial:

_mm512_(add|xor|ror)_epi32maps directly to the corresponding operations, most instructions have 1c latency and 0.5c throughput, and SHA-2 internal parallelisms can absorb that latency. - Logics can be implemented in ternary logic

_mm512_ternarylogic_epi32or plain boolean logic (LLVM will automatically lower them to ternary logic if possible). - The RustCrypto kernel is fully unrolled: keep them so to allow full pipelining.

Additionally:

- We can take advantage of the independence of the first $k$ rounds on the first $k$ message words and implement a const generic

BEGIN_ROUNDSthat allows caller to skip the first $k$ rounds in a DCE-friendly manner. - Mark the function as

#[inline(always)]to allow cross-function inlining and constant propagation. Tip:cfg_attrgate this out of unit tests and non AVX-512 targets to cut down compile time when you want quick iteration. - In case the nonce must cross message block boundaries, implement a slightly faster version where the message schedule is precomputed and broadcasted to all 16 lanes, we will explain the details of that optimization in the greedy padding section.

- Update the nonce after the hashing to give LLVM register allocator an easier job and minimize unnecessary register spills, which looks like paired

vmovdqu zmm, [rsp + ????]andvmovdqu [rsp + ????], zmmin assembly.

Brief Intro to SHA-NI

SHA-NI is, in contrast, a “horizontal” solution. You put the state horizontally into 128-bit XMM registers, and specialized instructions help you do the math in microcode.

Prevalence: Available on most modern x86 CPUs 2019 and newer and widely available across current cloud instances.

This one has well-known idioms as well that you can source open-source kernels from, generally speaking:

- States are packed into 2 128-bit XMM registers, one holds

ABEFand the other holdsCDGH, this takes advantage of the “rolling” nature of rounds and minimizes intermediate layout fixup instructions. sha256msg1andsha256msg2are used to update the message schedule.sha256rnds2is used to perform 2 rounds of computation.

The rhythm is approximately: sha256msg1, sha256rnds2, sha256msg2, sha256rnds2, repeat 16 times.

Additionally:

- Check Agner’s instruction tables, these instructions are high latency (about 3x their throughput). Which means in a miner setting we should be multi-issuing them across multiple independent messages. This can be done simply by adding a const generic

NUM_MESSAGESparameter to the kernel, then widening every register into an array of registers. Note that non AVX-512 systems only have 16 registers: so stop at 4 messages in parallel. - Implement a skip-rounds-by-4 and broadcast-message-schedule pattern as well.

Unfortunately SHA-NI is pretty finicky to work with as every instruction is high-latency and it is designed to be efficient when pipelined across very long messages, not repeated hash/reload cycles (also it is very awkward to “insert” nonces into XMM registers using only Haswell or older instructions). This can be seen on almost every hardware-assisted OpenSSL benchmark output as well where the throughput is very low when message length is short. So most of my experiments concentrated on using a software AVX-512 kernel.

Implementation Details

These are tricks I used in hooking up the kernel into my solver:

Common Tricks

- Align generously: better safe than sorry.

- If in doubt, check assembly output and instruction tables.

- Use microbenchmarks and static analysis tools like perf and llvm-mca to find hot paths and slow sequence patterns.

Round-Granular Hot-start

Recall from the SHA-2 overview, if the final message start at byte $P$, the first $\lfloor \frac{P}{4} \rfloor$ rounds can be precomputed. In code you will have a function that pre-runs the a given number of rounds:

| |

Greedy Padding

Since the nonce format is an ASCII decimal string, there is flexibility in how the search can be structured. Due to this we can apply these greedy strategies:

A total of 9 mutating digits is usually enough to find a solution. This can be computed using geometric distribution:

| |

We can solve up to difficulty 6 with virtually guaranteed success, and 97.5% success rate at difficulty 7 (the same challenge would have taken more than 20 minutes on a 200kH/s browser-based solver and would certainly expire even if someone were to set such a high difficulty-at that point people who manage to solve it are almost certainly more likely to be using bots than real browsers).

In reality if any padding digits are used-and we use them GENEROUSLY-we can just increment the padding and get additional keyspace, so success is almost guaranteed at any difficulty.

Padding strategies (all padding use an initial digit of 1 and then zeros):

First priority: avoid inter-block mutations as much as possible-if the 9 digits can be “pushed” to the next block, append constant digits to do that.

Second priority: If you use SIMD, keep the starting part of the search aligned to 32-bit boundaries, for example my AVX-512 kernel uses a 2-byte lane discriminator and 7-digits of incrementing nonces: so I pad to an offset of 2 modulo 4: this way the 2 lane IDs stay in one register and the 7-digits has fixed layout, paving ways for smarter nonce encoding optimizations.

Third priority: If there are space for more than 4 digits, push 4 digits of padding digits: allows one more round to be precomputed.

Improvement: Up to 13 out of 64 rounds can be precomputed depending on how long the nonce can be stretched out, although for 128 byte messages only 2 can be precomputed-you can maybe pre-compute one more if you really specialize on that message layout but I want a generic solution so I accepted this little inefficiency.

| Salt Len (mod 64) | Rounds Saved | % of total rounds Saved |

|---|---|---|

| [0,4) | 2 | 3.125% |

| [4,8) | 3 | 4.6875% |

| [8,12) | 4 | 6.25% |

| [12,16) | 5 | 7.8125% |

| [16,20) | 6 | 9.375% |

| [20,24) | 7 | 10.9375% |

| [24,28) | 8 | 12.5% |

| [28,32) | 9 | 14.0625% |

| [32,36) | 8 | 12.5% |

| [36,40) | 9 | 14.0625% |

| [40,44) | 10 | 15.625% |

| [44,48) | 11 | 17.1875% |

| [48,54) | 13 | 20.3125% |

| [54,60) | 0 | 0% |

| [60,64) | 1 | 1.5625% |

Offsets for common SHA-2 PoW browser captchas for your reference:

Constraints: Anubis server can only accept int range nonces, which means 31-bit on 32-bit platforms and 63-bit on 64-bit platforms, however since the vast majority of servers are 64-bit, for a demo we can assume 63-bit nonces will be accepted.

Feedback Elision

Observe that:

- Anubis requires the output to start with enough zeroes.

- SHA-256 MD construction output is the state words concatenated in big-endian order.

- It is highly unlikely a server will deploy a difficulty of 8 or higher (takes about 5 hours on 200kH/s).

We can simplify the successful condition into $H_0 < 1 \ll (4 * D)$: as the rest of the words do not matter.

Now back-propagate the unused portion of hashes, since $H_1 \cdots H_{8}$ do not matter, feedforward terms for them also do not matter and thus do not need to be saved or computed.

Improvement: Saves massive register pressure budget on AVX-512.

If we want 64-bit search (i.e. difficulty 8 or higher), we can use the unpack sequence (note that this shuffles the original lane order so we need to fix that up with a LUT lookup to translate the virtual lane index into the original lane index):

| |

_mm512_unpacklo_epi32“Unpack and interleave 32-bit intergers”: so we put B at the least significant position and A at the most significant position (note little-endian, so low address is least significant). (RecallBis simply rolled fromAin the second-to-last round, so it has much less latency to compute thanA).met_target_testgets lowered into a singlekortest k0, k1(OR Masks and Set Flags) instruction that setsZFdepending on if any of the mask bits are set, 1c on most modern CPUs and can be uop-fused into the Jcc after it.

In assembly it looks like this:

| |

Template Instantiation / Monomorphization

Since the position to inject dynamic data can be different and registers cannot be indexed using a runtime value: monomorphize specialized kernels are very important.

Constant branching statements are reliably DCE’ed so you can use them to implement diverging logic with no runtime overhead.

Since this function runs for a long time (at least 200ms) before returning, adding never inlines are useful for producing stable, comparable and readable assembly: otherwise LLVM may underestimate the size of the inner function (recall we forced inlined a fully unrolled SHA-256 kernel) and inline the whole thing into the outer function causing code size and compile time bloat.

| |

Improvement: Lose to scalar solutions if not done!

Dealing with Double-Block hashes

Since MD construction needs 9-bytes of free space as padding/suffix, some awkward salt lengths will lead to unavoidable double-block hashing as no amount of digit padding can push the mutating part into its own block. This happens for about 10% of possible salt lengths-and the current Anubis 128 byte salt length is not one of them.

Instead, we will go for a secondary solution that pad the message so that the layout is exactly:

- The salt itself.

- Padding digits.

- 9 mutating nonce portions.

- Block boundary.

- Zeroes.

- 0x80

- 64-bit length

We will precompute the message schedule for the second block (and pre-add the round constants), and use the precomputed message schedule variant for that.

Improvement: about 20% improvement in throughput on the second block, ~10% overall.

Nonce Encoding

ASCII div_mod chains are expensive, while LLVM generally can factor them out as independent operations, they generally do not vectorize them, especially if the output is not in natural order (for example in SHA-2 it needs to be converted to big-endian order, which can lead to discontinuous byte poke patterns).

However, in greedy padding priority 2, we try to ensure the exact position of the mutating part and thus the byte offsets. Since the byte after the 7 mutating digit is always 0x80. We can hoist the “convert 7 digits to ASCII, append 0x80 then convert to big-endian” chain out of the loop and vectorize it.

The straightforward way is division using constant multiplications.

Improvement: about 10% improvement in throughput for AVX-512 for single block workflow only: for double block workflows the second block does not depend on the message schedule and thus using interleaved scalar updates are faster.

Macro and Compiler Assist

Use constant block patterns generously to avoid magic numbers:

Compute an ASCII ‘0’ and placeholder/sentinel byte mask iteratively then use it as constant:

| |

Compute division magic numbers iteratively then use them as constant:

| |

Additionally, don’t bother with manually writing ternary logic: LLVM always lowers bitwise logical combinations that only depend on 3 values into ternary logic. if you want you be explicit you can use this macro to find the constant (it is basically a truth table lookup):

| |

Improvement: Life quality-no magic constants to get wrong subtly.

Benchmarks

The full benchmark log and code is available in the appendix and code repository, here is a short summary.

Benchmarks are ran on AMD Ryzen 9 7950X unless otherwise specified. Anubis is built using official Makefile rule with no special flags with difficulty set to 4 unless otherwise specified.

I also appended a binary nonce benchmark since they do have a WIP on that, but to my best knowledge it is not on release track yet nor deployed anywhere.

Single Threaded

| |

The single-threaded throughput for OpenSSL with SHA-NI support is about 12.94 MH/s (828.2MB/s) single block, 42.00 MH/s (2.86 GB/s) continuous.

For us we have single thread:

| Workload | AVX-512 | SHA-NI | Chromium SIMD128 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SingleBlock/Anubis | 85.75 MH/s | 62.19 MH/s | 14.74 MH/s |

| Binary nonce (16 bytes) | 97.87 MH/s | 78.10 MH/s | Not Tested |

The throughput on 7950X for Anubis varies between about 100-200kH/s on Chromium and about 20% of that on Firefox, this is corroborated by Anubis’s own accounts in their code comments using 7950X3D empirical testing (grep for 7950X3D in their codebase and this PR).

Multi Threaded

The peak throughput on 7950X reported by openssl speed -multi 32 sha256 is 239.76 MH/s (15.34 GB/s) single block, 1.14 GH/s (73.24 GB/s) continuous.

| Workload | AVX-512 | SHA-NI |

|---|---|---|

| SingleBlock/Anubis | 1.485 GH/s | 1.143 GH/s |

| Binary nonce (16 bytes) | 1.525 GH/s | 1.291 GH/s |

On EPYC 9634 with better thermals, OpenSSL has 598.28 MH/s (38.29 GB/s) single block, 1.91 GH/s (122.54 GB/s) continuous.

| Workload | AVX-512 | SHA-NI |

|---|---|---|

| SingleBlock/Anubis | 3.387 GH/s | 2.09 GH/s |

| Binary nonce (16 bytes) | 3.826 GH/s | 3.15 GH/s |

Mitigations?

This post focuses on measurement, reproducibility, and native‑side optimization of proof generation. It does not offer advice on how to “fix” or harden Anubis.

Why no mitigation list?

- Different objectives: I see Anubis as a QoS/request-shaping mechanism, while the project positions it as a security control. Advice across mismatched goals tends to be unhelpful.

- Out of scope: The topic here is provers and throughput. Server architecture deserves its own work and would either crowd out the core content or be too tangential/unelaborated that isn’t more useful than AI-assisted analysis.

- Ethics: I have reservations about monoculture bot‑deterrence and user‑cost externalization. I don’t want to contribute to making such gatekeeping more “effective”.

Related Work / Similar Projects

- David Buchanan’s anubis_offload: An OpenCL solution. No offical hash rate numbers but seems to be approximately 1GH/s (not sure if transfer latency is included), although requires a whole GPU and transfer latency.

Appendices

Code Availability

The code is available on GitHub under the Apache 2.0 license.

Go pprof top10

| |

Caveat: We didn’t benchmark alternative KV-stores such as bbolt or Valkey here. Architecturally, bbolt is single‑writer and degrades under heavy delete churn; Valkey adds a network hop and runs commands on a single event‑loop thread with optional persistence/TTL costs. Thus we believe it is unlikely to perform significantly better than the default in-memory kv store. ↩︎